By Jorge Alberto Perez

For ARC Magazine

There is hair between beauty and love.

There is hair between beauty and love.

Let me clarify – these are subject headings on the website of Essence Magazine and “Hair” is right in between the two biggies for any popular culture, lifestyle guide – “Beauty” and “Love.” The other categories are things like celebrity, fashion, point-of-view and photos. Hair is the only body part.

The featured photo slide-show in “Hair” today, the day I am writing these lines, is titled “Looking Good” and is subtitled “Hot Hair: 100 Best Summertime Styles.” Of those 100 hairstyles, only two are Afros and a paltry 5 more are naturally curly hair. The rest, the other 93, have been altered – relaxed, straightened, permed, hot-combed, flat-ironed…

Such is the currency of African-textured hair – definitely under-represented, culturally devalued, and almost universally negated.

This year the surgeon general Regina Benjamin called for hairstylists to come up with do’s (as opposed to don’ts) for African-American women that are easier to exercise with. It turns out that since they have invested money and lots of time to relax, perm, hot-comb, and flat-iron their naturally curly locks into straight and silky hair, women choose to not exercise so as to not mess up their hair. So the surgeon general is talking about hair as a detriment to women’s’ health. And not women in general, but women of color. Studies show that fifty percent of African-American women over 20 are overweight or obese and thus suffer from the myriad diseases associated with those conditions.

You may be asking what all this has to do with Art? After all, you are reading it in an art magazine, one without a “hair” section. For it to make sense I have to go back to June when I went to the Museo del Barrio’s 6th Biennial exhibit of the “most innovative, cutting-edge art created by Latino, Caribbean, and Latin American artists currently working in the greater New York area” (quoted from the press release) where there is a lot of new but somewhat predictable Latino art on view – much of it colorful, visually bold, fun, urban, street-savvy. You might think you have seen a lot of it before, until you see the work of Firelei Baez.

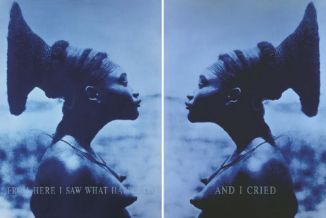

From across the gallery I see, what are those? Stains? Brown stains on a white background? How many? 28…29…30…31 perfect squares about 14” across. I don’t approach yet. The monochromatic paintings are a whisper in a cacophony of color and texture. For that reason alone one is drawn to them. They seem amorphous and I think of Helen Frankenthaler’s stain paintings of the 1950’s. Thin boundary-lines of pigment delineating muted watered-down brown hues against a white background…and I must admit I am smitten by the layout. A calendar grid, yes, that’s what it is, but a calendar of what? My eyes follow the borders of the paper-bag brown stains, darting from one to the other and suddenly I see it. They are silhouettes. A woman’s head, her hair spilling and spinning in many directions. Every “day” the shape is different. I step closer and realize the paintings are starting back at me. Realistically rendered eyes float in the abstracted shapes of the face, head and hair, suddenly piercing through the surface of the painting. I am transfixed, like when you accidentally look at the ubiquitous security camera eye-balls in every/any store, building, elevator, and you get that jolt of, what is it? Fear or self-consciousness? When you know someone, something, is looking back at you, evaluating your behavior. The 31 pairs of eyes are upon me. I feel scrutinized, inspected, examined, evaluated. Wow, didn’t expect that visceral, recoiling sensation.

That was the first time I saw Baez’ work and I was hit over the head with it. On the one hand I already found a certain peace in the multiple paintings in almost identical tones of that distinctive brown, curiously soothing. But once I was aware that each shape was a person and that she had eyes, the power shifted away from me. Despite being reduced to a single tone of color without the topography of a face, this person stared right back at me defiantly. I was no longer a consumer taking stock of what I get about a work of art, scrutinizing, inspecting and evaluating… until that strange thing happens when you feel furtive glances looking back. Are the eyes blinking? It is impossible to see them all at once.

The work is titled “Can I Pass? Introducing the paper bag to the fan test.” Cryptic I know, but bear with me. Firelei is the child of Dominican and Haitian heritage. She grew up first in the rural countryside of the Dominican Republic and later in the American South. In each place she learned where she fit into the spectrum of skin color and how it parlayed into her social status in any number of loose or rigid group structures. She learned also of some archaic racial “tests” that helped determine if a person, (read: woman) is racially “impure.” The “avanico” or “fan test” specifically addressed the question of hair. When fanned, European/white hair will flow back. African-textured hair will not. The discovery of “blackness” by this means was grounds for legally justifying a divorce in the eyes of the law in the Dominican Republic. The idea seems absurd now, but it wasn’t that long ago that it was an actual scientific-ish stunt upon which lives turned. The “paper bag test” is even more nefarious as it arises from within the African-American community as an evaluation used for social stratification within organizations, mostly sororities and fraternities. This is the pigmentocracy – where the status hierarchy of a group is based on the lightness or darkness the skin. A particular brand of intra-racism that alters notions of beauty and (self)-love for generations to come.

With her “Can I pass?…” piece Baez is, on one level, making a pretty straightforward commentary on historical practices concerning visual markers of race. She wakes up, prepares herself to meet the faces that she meets, goes out into the world and upon returning home she snaps a picture or two to capture the shape and texture of her hair, and settles into the meditative act of painting as accurately as possible merely two aspects of herself – one signifier of race and one of race and gender. She works to match color of her skin as a single field that outlines the shape of her head. Can she pass for white on that or any given day were she to need to? If darker than a paper bag she will not. And what of her hair? Would the fan test prove that her hair wouldn’t flow back? We can just look at the silhouettes and judge for ourselves which days she may have. According to Baez, this idea of hair flowing ‘naturally’ is still a standard held in most Dominican beauty salons and is part of the disguise women of color have learned to wear.

On a deeper level, however, we are confronted with what could be Baez’ struggle to occupy space physically, culturally, and even emotionally and the tensions generated between the willful abstraction of her self-portrait versus reduced representations of the signifiers of beauty or lack of it, in the dominant culture. Is it her absence or presence that she is questioning every day in this calendar system of painting? She is certainly reduced, redacted even, but is she documenting her silence or her expression? Her goal is to perform this act of painting as document for a year to further complicate the discrepancy between the signifier and the signified.

Were her eyes not painted with such attention to detail I might be inclined to say the calendar of skin color and hair silhouette is a retreat into victimhood. But those eyes… The eyes are empowered to penetrate. They look out and condemn the viewer to the same level of scrutiny Baez herself is subjected to. They are defiant, but often also cold and indifferent. This is the expression with which she looks into the mirror to qualify an element of humanity in an otherwise scientific document. We become stand-ins for Baez herself and are suddenly privy to what it feels like to judge yourself according to physical standards that are contrary to your own genetics. In this way, the internalization of color/race consciousness is transmitted very powerfully and pulls forward the lineage of other artists like Ellen Gallagher, Carrie Mae Weems and Kara Walker. Like them Baez openly challenges the cultural punishments attached to women of color, whether self-perpetuated or not. But she also takes exception to the strict morality associated with the control required by the patriarchal society – a control of uniform standards of beauty that supposedly, if we are to believe the advertisements, will beget love. Baez also seems to refute the myth of the sexualized, wild-haired Latin Medusa with the same brush strokes. She inhabits the possibility of change in her eyes, the possibility of subverting these social and cultural structures through a systematic documentation of these two physical attributes that manage to not define her. Because no matter what, it is the vibrancy of soul in her eyes that we are drawn to in these 31 paintings and both the subject and viewer are redeemed.

www.jorgealbertoperez.com